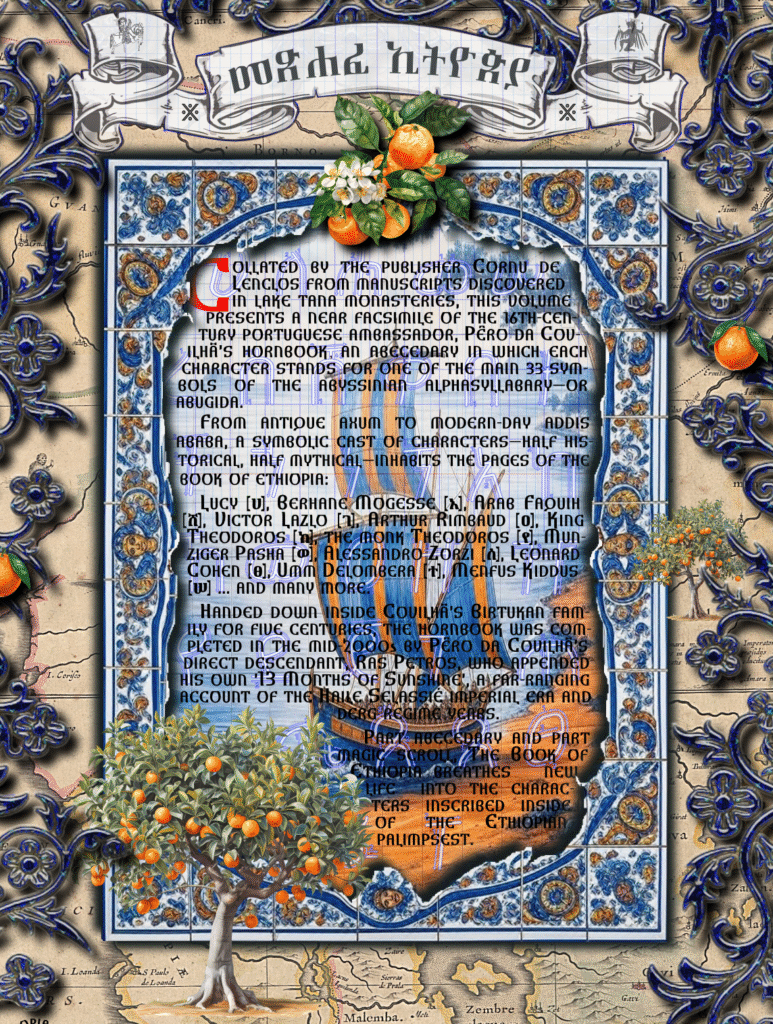

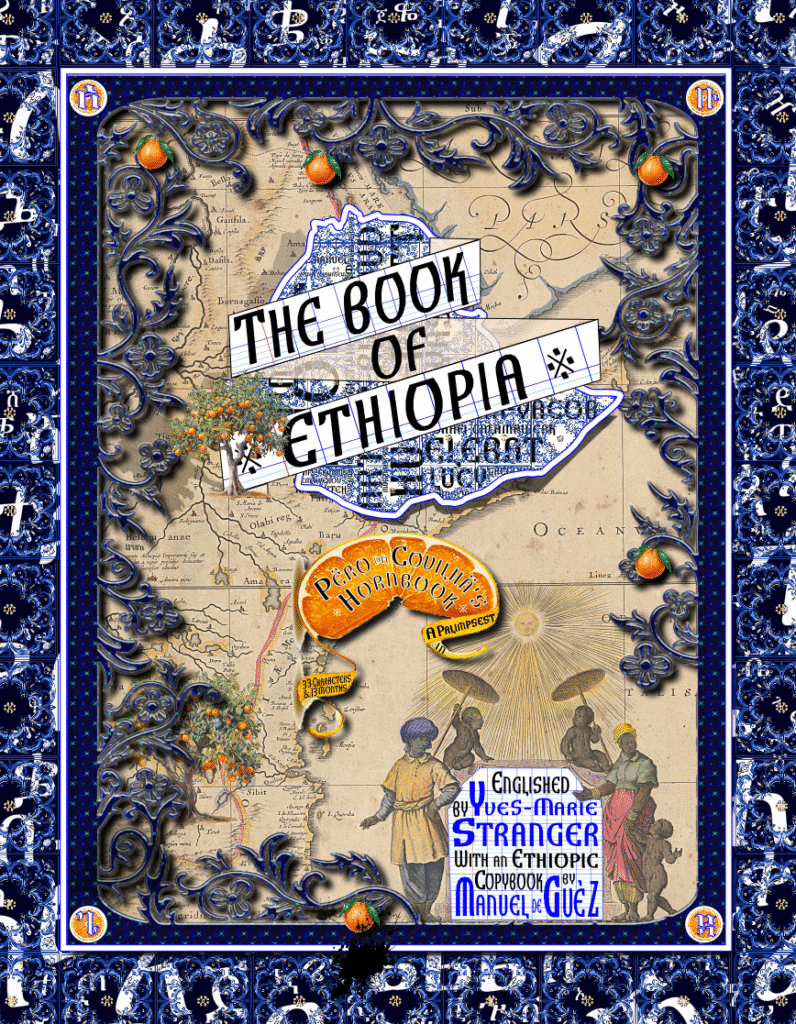

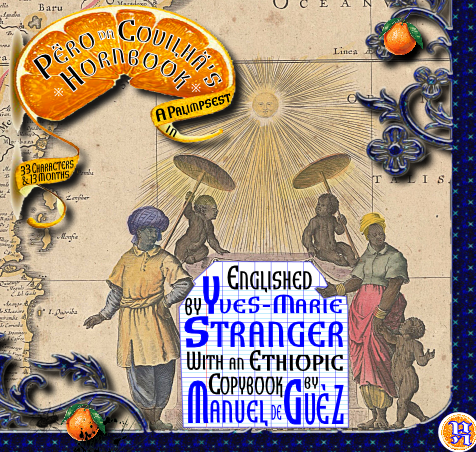

THE BOOK OF ETHIOPIA

PÊRO DA COVILHÃ’S HORNBOOK

፠ A PALIMPSEST IN 33 CHARACTERS AND 13 MONTHS ፠

፠

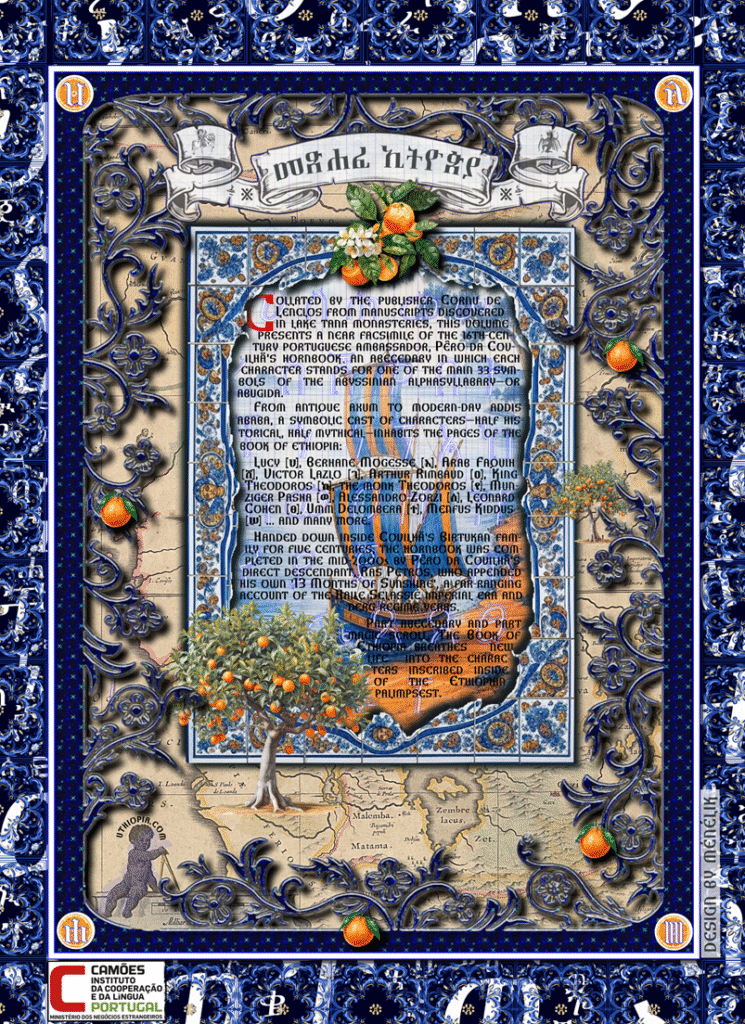

፨ The story begins when Yves-Marie Stranger receives an outline of PÊRO DA COVILHÃ’S HORNBOOK in a « cahier Seyès » sent to him by by Jean-Michel Cornu de Lenclos. The old fashioned exercise book contains a facsimile of the long lost memoirs of the Portuguese traveller, an account preserved for five centuries in an Ethiopian hornbook*, by PÊRO’S last descendant in Ethiopia, the mysterious ‘RAS PETROS‘.

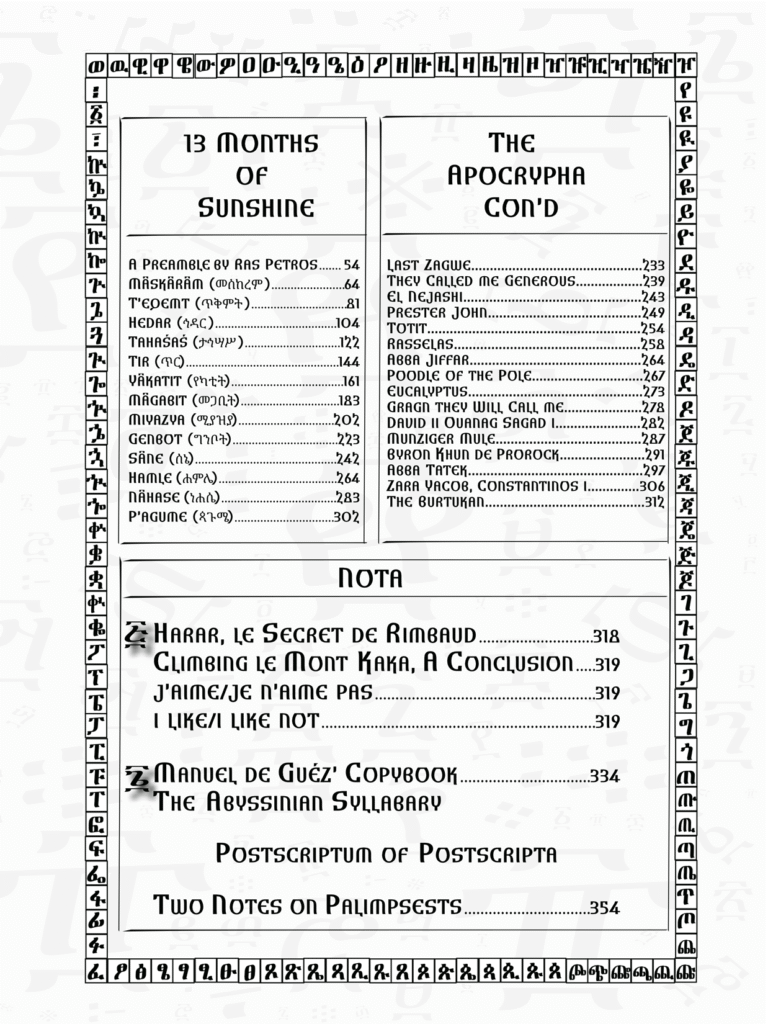

THE HORNBOOK includes sketches of Ethiopian historical characters, associated to numerological annotations from a forgotten work of the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, L’Arithnomancie Ethiopienne. Ensues a romp through the pages of Ethiopian history, that will ultimately lead to an excursion to the summit of Mount Kaka, a 4 000 high peak located in the Rift Valley.

፨ With a prologue by the distinguished scholar MANUEL DE GUÈZ.

*Hornbook. n.s. [horn and book.] The first book of children, covered with horn to keep it unsoiled.

‘He teaches boys the hornbook.’ (

A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755 (‘Dr Johnson’s Dictionary‘)

THE BOOK OF ETHIOPIA is a precious account of the great historical events of those times, and later centuries, as the Portuguese explorer’s descendants continued to use the hornbook to collect events and stories henceforth. As such it constitutes a chronicle of five hundred years of Ethiopian history.

፨ Part historical fiction and part magic scroll, THE BOOK OF ETHIOPIA compounds tentative fact and patent fiction to breathe a new life into the characters of the Ethiopian palimpsest.

፠

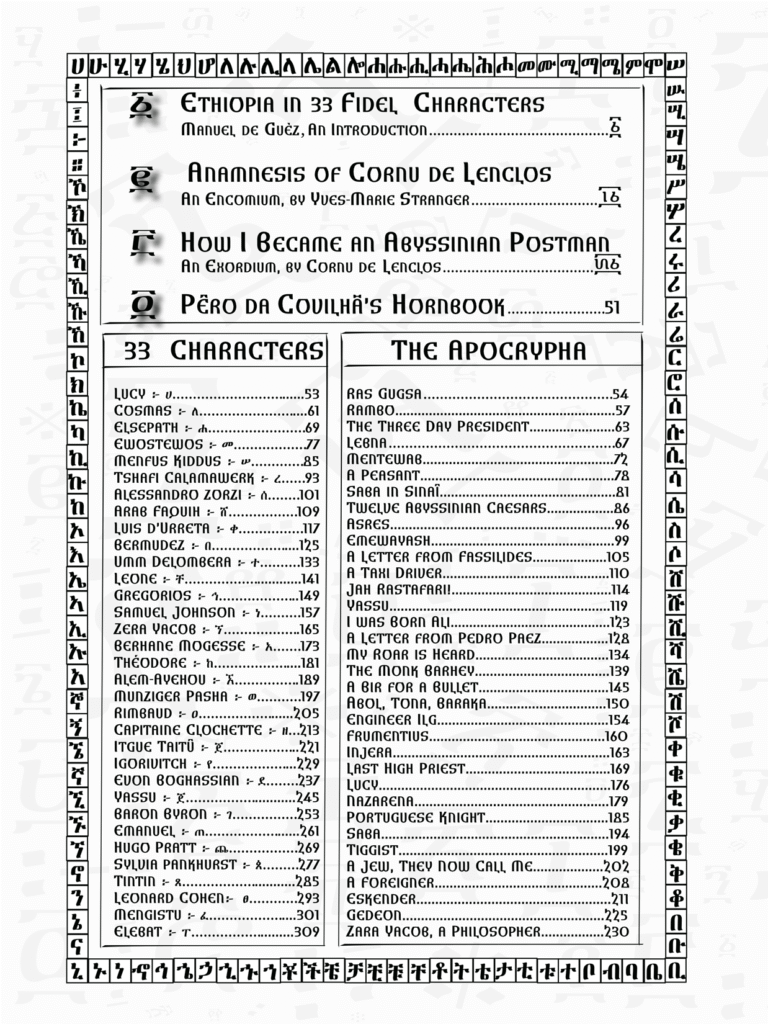

፴፫ (33) LIVES-LETTERS-CHARACTERS

FROM ሀ TO ፐ

፠

፦ SPELLING OUT THE MANY LIVES OF VICTOR LAZLO [ገ], RIMBAUD [ዐ], KING THEODOROS [ከ], the MONK THEODOROS [የ], MUNZIGER PASHA [ወ], ALESSANDRO ZORZI [ሰ], ARAB FAQUIH [ሸ], LEONARD COHEN [ፀ], UMM DELOMBERA [ተ], MENFUS QIDDUS [ሠ] AND MORE…

፠

፠

FROM THE PROLOGUE OF MANUEL DE GUÈZ

” (…) so that, of course, one can wonder, not only at the question of what is an Ethiopian – but if there even ever was such a thing. For nations are similar to the knife of yore, still sharp after 2 000 years. The handle of which was refashioned, then the blade, and this ad infinitum.

And yet – we would like to believe that we are one and the same with the people of yesteryear. In this view, the English are, at all times, the English, and the Ethiopians are, and always were, the Ethiopians. And so, we continue to carve up our histories with this blade – not realising that it is our own razor sharp utensil – our inward eye – which is perpetually refocusing on the needs of the present.

We only delve into the abyss of time, in a desire to shed light on our present predicament – so that I would vouch to say that the English yeoman, the Inuit of Ultima Thule and the swarthy Abyssinian never truly did exist – or if so, never in any form that we ourselves could possibly unravel – The past is not only a foreign land, it is a country peopled by foreigners.”

፠

FROM THE 33 CHARACTERS

መ ፣ EWASTEWOS, A HERETIC

፦ Ewastewos partook of sorghum porridge, such as the other little childrens, and he played at the game shepherd & flock, with clay and white stones, such as is the nature of all little childrens. And, similar again to all other children, he went about naked, without being ashamed, until the age of six years, age at which he was covered with a piece of rough fabric that held two holes for the arms and one for the head.

This is also the age at which he was brought to the priests, to learn his syllabary, and the age at which he stopped having his head shaven. The first morning, when Ewastewos sat himself down under the fig tree where the lesson was given, the swarm of bees congregated above him once more, and pulsated in unison to the chanting of the fidels, and the child Ewastewos did not fumble these fidels similar to the other pupils, but to the contrary enounced them to perfection.

On the second day, this swarm did not return but Ewastewos now possessed his syllabary in its entirety and could read it clearly without even a single mistake. On the third day, he read the Psalms of David in Ge’ez, and he knew them. On the fourth, he initiated his reading of the Old Testament, and on the fifth completed the New (…) ።

From the Life of Ewastewos

፠

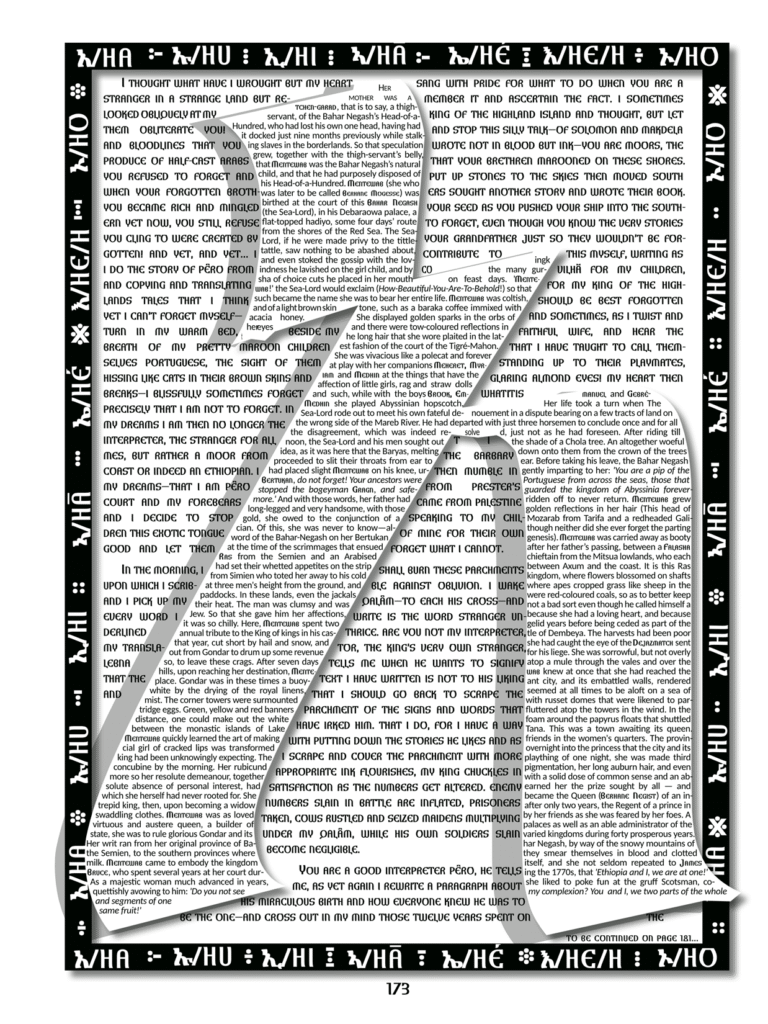

አ ፣ MENTEWAB, A QUEEN

፦ Mentewab was carried away as booty at the time of the wars that ensued her father’s demise, between a Falasha Ras from the Semien and an Arabised chief from the Mitsua lowlands, who each had set their whetted appetites on the fertile strip between Axum and the coast. It is this Ras from Simien who bundled her away to his cold kingdom, where flowers bloomed on shafts at three men’s height from the ground, and where apes cropped grass such as sheep in the paddocks. In these lands, even the jackals wore red-coloured coats, so as to better keep their heat. Mentewab knew the man, who was clumsy and rough, but not a bad sort even though he called himself a Jew, so that she gave him her affections, a little because she had a loving heart, and also because it was so chilly (…) ።

፠

፠

፠

ቸ ፣ LEONE, A PAINTER

፦ Leone was a wastrel from his very first years, that he ill-spent in rapine and acts of skulduggery in the taverns and markets of Florence. He was born during a lull in the war between the Black and the White Guelfs, and as the paroxysms of violence smouldered under the gutted houses, it was a good time for tricksters and all forms of thievery, which was propitious for Leone, as he was a scoundrel, and not a brave one either.

Defenestration and throttling had become so commonplace in Florence in those years that ground floor rents had tripled in price, and soothsayers peddled copper necklaces they lauded as foolproof charms against the exactions of the garrotter. Leone’s father did not trade in charms himself but was a swindler too as, a baker, he had no compunction in debasing his wheat with chestnut and acorn. From this chicanery, Leone acquired a lifelong dislike of blended foodstuffs and was to persist, to the term of his natural life, in desisting from partaking of any dishes not prepared in his own kitchens – nor was he ever to accept a dwelling reached by a fleet of stairs. This was to later prove itself convenient, as in Ethiopia all foods are basic, and all houses are built of a piece (…) ።

From the Life of Leone

፠

ጠ ፣ BARIAW, A LEBA SHAI

፦ He was truly born to the Begemder roads, where he forged his first souvenir: a half dozen men in blue loincloths that harry before them a slave gang. These slaves are toweringly tall, with etchings on their naked bodies. They bear an elephant tusk on each shoulder, the stumps festooned with pink flesh and scraps of grey skin. The men in this slaving party sing merry songs, rhythmic couplets they gaily make up, on the riches they shall procure, from the ivory and the towering giants, on the Gondar market. Emmanuel is perhaps four years of age. He is therefore born at the beginning of the 20th century of the Franks. He travels with a salt merchant, who trades in amole, rectangles of crystal salt mined in the Danakil desert and hauled to the markets of Gojjam and Begemder, from the staging post of Kombolcha in Wollo ።

From the Life of Bariaw

፠

ደ ፣ EVON BORGHOSSIAN, A FRENCH HORN

፦ Then came the Rhinoceros Express and its Imperial salon-restaurant, in which the Maître d’Hôtel, a native of Bordeaux who was called Rouget but only answered to the name Ducasse (because such had been the name of the king’s first cook) concocted for them mousse au chocolat “à la Gojjamite.” The merry train soon pulled into the tiny monarch’s diminutive capital, with much use of the steam whistle at dawn, and this capital, such as the railway itself, was like a shiny toy, a model town blanketed in a pungent mix of cow dung smoke and eucalyptus vapours.

But oh, what fun! Open cars awaited them in the station park, and the forty orphans were whisked away to the palace, where they were at first housed in the attics, before being pensioned off with the Armenian families of Addis Ababa. For in those days, the Armenians, together with the Greeks, were the empire’s craftspeople: they were distillers and photographers, tailors and shoemakers, jewellers and stonemasons. Soon, in earshot of the Apostolic Armenian Orthodox Church of the Ethiopias, an Armenian language school was opened by a few masters, who had returned with freshly minted certificates from Marseille, just above the Ras Mekonnen Bridge, plumb in the middle of Seretegna Sefer (the neighbourhood of the workers). The forty orphans were of all the feasts, all the celebrations (…) ።

From the Life of Evon

፠

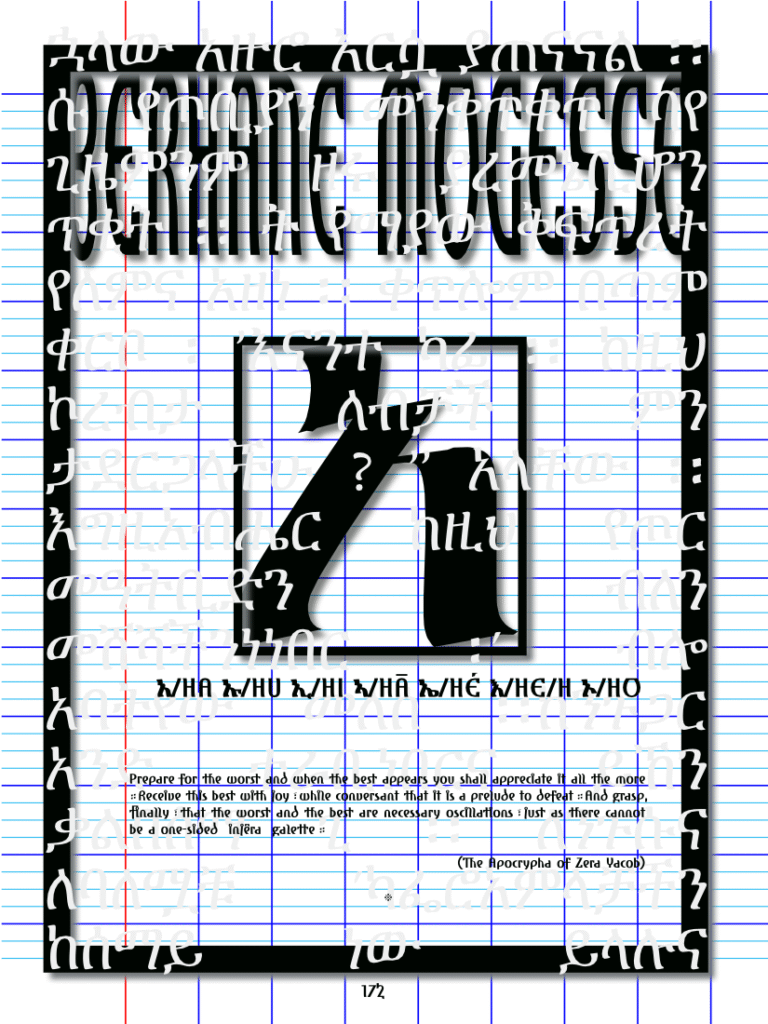

ኘ ፣ ZERA YACOB, A PHILOSOPHER

“Raw meat, pepper and flasks of mead, that’s what we need!” imparted a hurried Zera Yacob to his disciple Baêdeu Maryam. “But we are in Lent,” the latter remonstrated timidly. “Splendid!” exclaimed his Master: “the disapproval of all shall render our feast all the more delectable ። ”

From The Apocrypha of Zera Yacob

፠

ፈ ፣ MENGISTU HAILÉ MARIAM, KAKISTOCRAT

፦ And so it passed that the children of the House-of-the-Mule taunted Mengistu, branding him with the soubriquet southern bastard, calling him a bula-gruel-slurping-runt, and adding, what is more, that his grandmother, who now wore the yellow skull cap of a nun on her shrivelled head, and who had taken the name Guebre-Maryam, (Slave of Mary), was in reality called Totit, which means Little Monkey, and that she was a slave in her youth, which, for being injurious, was the plain truth. The grandmother herself had no truck with these stories. She was a very shortish woman, with a spark of mischief in her eye, and she herself had a love of good gossip and slander. But Mengistu Haile-Maryam (Government-Force-of-Mary) grew up withdrawn and resentful (…) ።

From the Life of Mengistu Haile-Maryam

።

፨ Yves-Marie Stranger is a writer and translator. He is the editor of Ethiopia through Writers’ Eyes (Eland Books), and the author of A Gallop in Ethiopia, and Ces pas qui trop vitent s’effacent (L’Archange Minotaure). He translated the books Menelik and African Train, Djibouti-Addis Ababa (Hugues Fontaine, Amarna).

His exhibition ‘The Abyssinian Syllabary’ was shown both in Ethiopia (Addis Ababa, Alliance Éthio-Française) and in France (Carré d’Art, Nîmes). You can also listen to The Abyssinian Syllabary on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or Youtube.

THE BOOK OF ETHIOPIA, PÊRO DA COVILHÃ’S HORNBOOK

Hardback / 370 pages / 20×27 cms.

Published with the support of the Embassy of Portugal in Ethiopia and the Camões Institute

።