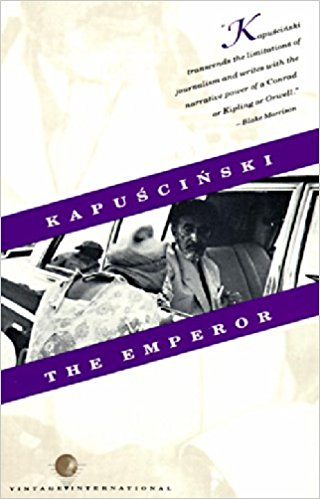

Ryszard Kapuściński, The Emperor, Downfall of an Autocrat

While I was careful to preface Ethiopia through writers’ eyes with the following caveat:

“Like all those possessing a library, Aurelian was aware that he was guilty of not knowing his in its entirety.”

The Theologians, Jorge Luis Borges

It rests that as soon as a book is launched into the world, be it from the flat topped amba of Mount Abora, a multitude of overlooked works immediately begin to form a perilously high tower of their own.

Here then, after the canon of Ethiopia through writers’ eyes, the apocrypha:

Ryszard Kapuściński, The Emperor, Downfall of an Autocrat

“One important and useful characteristic of the new people was that they had no past, had never taken part in conspiracies, trailed no bedraggled tails behind them, and had nothing shameful to slide in the lining of their clothes. Indeed, they didn’t even know anything about conspiracies, and how were they going to find out about them if His Noble Majesty had forbidden the history of Ethiopia to be written? Too young, brought up in distant provinces, they could not know that in 1916 His Highness himself had come to power thanks to a conspiracy; that aided by European embassies, he had staged a coup and eliminated the legal heir to the throne, Lidj Yasu. […] Many other events come to mind, but in the Palace it was forbidden to talk about them, and, as I said, the new people could not know about them and did not show much curiosity. And as they had no old connections, their only chance for survival was to keep themselves tied to the throne. Their only support: the Emperor himself. And thus His Most Extraordinary Majesty created a force that, during the last 10 years of his reign, propped up the Imperial throne that Germame had undermined.”

(Ryszard Kapuściński (1932–2007), Polish press correspondent, celebrated writer and, it is rumoured, Warsaw intelligence operative. His Emperor, Downfall of an Autocrat, on the toppling of Haile Selassie in 1974, after long being seen as a perfect exercise in reportage, has in recent years come to be reappraised as being more fiction than fact. But neither his putative allegiance to his country’s intelligence services or alleged fictionalisation of his account of the inner workings of an autocracy detract from the brilliance of his work. If The Emperor is a work of the imagination—and not a collection of testimonials, as claimed by Kapuściński—it is then a better work still. The analysis of the inner workings of Ethiopian society retains its pertinence today)

Buy the book on Amazon.