Gudu the Highland Horse Market

When I first went to Gudu just a few years ago, there were a few mud houses, and no electricity. Today, Ethiopian pop blasts out of three or four coffee houses – and they even have espresso machines. A hotel of sorts has beds for 25 birr a night. There was no road either back then – you could walk or you could ride a horse.

Gudu has one foot in today’s Ethiopia, and one foot in yesterday’s Abyssinia. It is a quintessential highland town – just 30 kilometer as the crow flies from Addis Ababa. In an old market photo in Wax and Gold, Donald Levine’s penetrating study of mid 60s peasant life in Menz, a high plateau above Debre Berhan, the first thing you notice in the picture is the simplicity of the clothing – gabis and shorts, nearly no shoes – the second is the tiny size of the ‘stalls,’ and the third the homogenous nature of it all. Me, my blanket wrap, a plow (and perhaps a Bible). Is anything else needed to form a life? Not in 1960s Menz, that’s for sure. In his book, Levine creatively uses the Wax and Gold theme, which refers to the technique of casting a jewel by filling in a shape with precious metal. This melts the wax of the form away, leaving only the gold of the desired jewel. In turn, the technique is known to all Ethiopians who use it in word play and double-entendres, to say without saying, to criticize openly – but in a concealed manner, and generally talk, or sing, or joke about taboo elements, or figures of authority. You say one thing but mean another, the apparent meaning being of course the wax, while the hidden meaning is the nugget of gold. Levine makes this widespread tendency to double-entendre a central force of ‘Ethiopian’ culture – and he questions whether it is a trait that will mix well with modernity.

Today, a market such as Gudu contains brilliant fabrics woven in the Pearl River area of China, batteries from Thailand that work a minute or two – I personally tested four last week in the space of ten minutes – candy and plastic shoes made in Ethiopia, red buckets and public photographers with digital cameras (pose now, get the print next week). The drab clothing of yesteryear has been replaced by bright colors for the women, and suits of blue and green for the men. All wear shoes. Buses drive into town in a cloud of dust in a blare of Orthodox Church music in the early mornings, and Ethio pop for the afternoon when they take their leave. Merchants come from far, and there is even a protestant preacher or two – on their backs and chests a pinned paper reads “Jesus is Lord.” On the green baize of the highland, the horse market is like a pool table – the horses are the balls glancing off on another in complicated moves, the punts studied and commented by all. But if the heart of the action is a horse kicking up dust, this apparent focus is a stratagem for other, more important going ons. The horse is ‘only’ a symbol, the lost wax of the heart of gold concealed underneath. A three band shot which everybody applauds – to then better turn and engage in the more serious acts of life – buying, selling, establishing status, concealing a wry smile. And buying plastic shoes for the first time. For all the market’s diversity and color, Donald Levine would probably feel quite at home. And, nearly fifty years after his book came out, with that niggling question about the possible clash between Ethiopian values and modernity, the jury is still out.

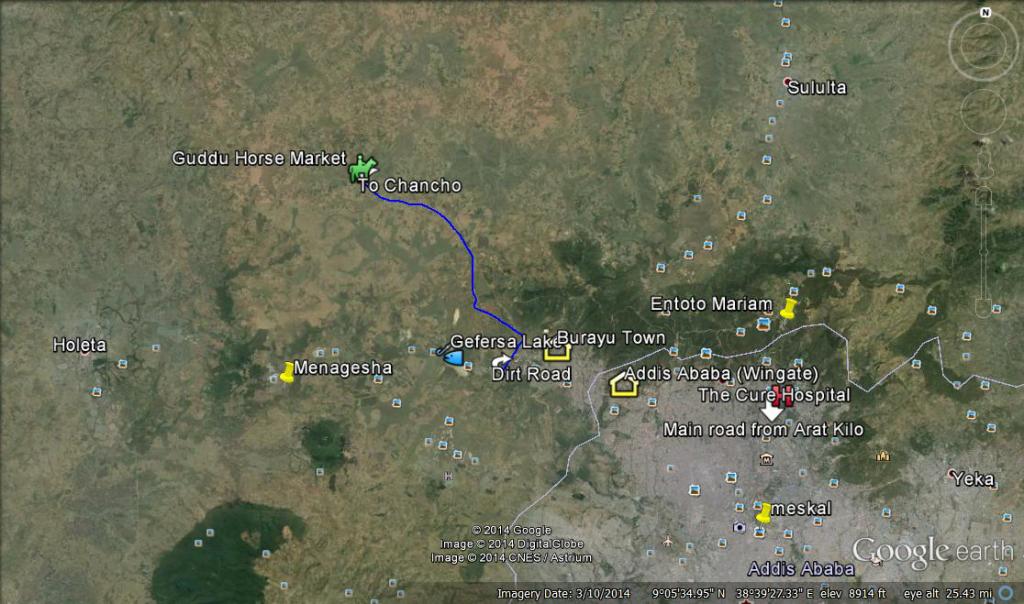

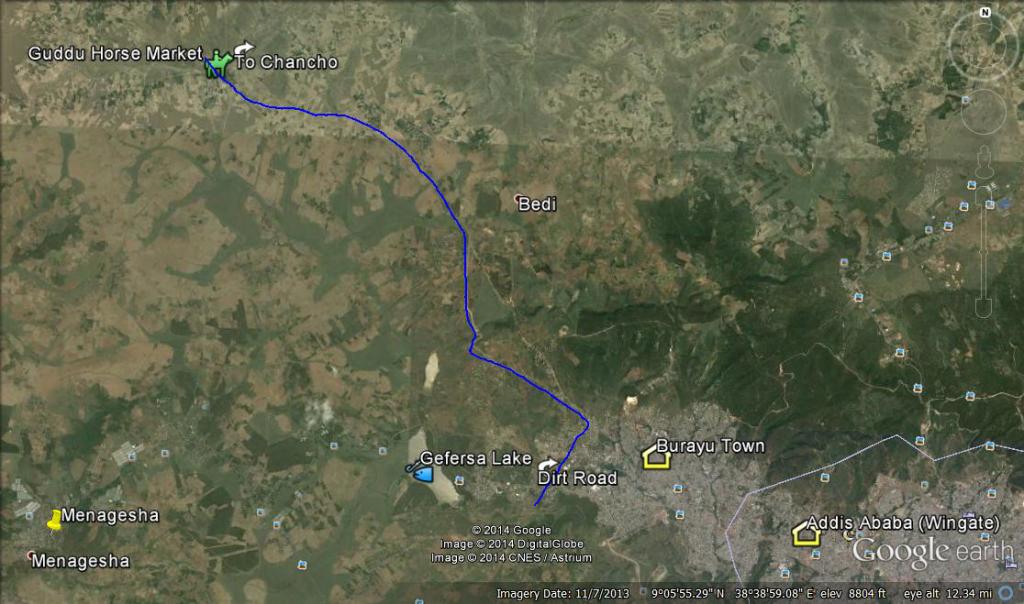

Gudu can easily be reached from Addis for a morning excursion. Plan the day if you want to buy a horse: